In the chapter on ‘the creation of the urban commons’, in his book Rebel Cities, the social geographer David Harvey admits that commons might need enclosures: “There is much confusion over the relationship between the commons and the supposed evils of enclosure. In the grander scheme of things (and particularly at the global level), some sort of enclosure is often the best way to preserve certain kinds of valued commons. That sounds like, and is, a contradictory statement, but it reflects a truly contradictory situation. It will take a draconian act of enclosure in Amazonia, for example, to protect both biodiversity and the cultures of indigenous populations as part of our global natural and cultural commons. It will almost certainly require state authority to protect those commons against the philistine democracy of short-term moneyed interests ravaging the land with soy bean plantations and cattle ranching. So not all forms of enclosure can be dismissed as bad by definition.”[1]

We would argue that enclosure has become a technical term for land grab, of what Marx called original or primitive accumulation and for privatization in general – from the sixteenth century onwards. Thomas More has been the first to protest against enclosures, it was the point of ignition of his book Utopia[2]. With the advent of neoliberalism there has been a new wave of enclosures: the privatization of all things public (like public transport, communication networks or power plants) and the commodification of everything (even knowledge, but also plants and seeds). Even if we are fully aware that a great Marxist scholar like David Harvey knows all of this (and even better than most), we deem it a bad idea to use the same term for the necessity to defend commons against overuse or ‘free riding’(as Ostrom calls ‘profiteering’) or depletion, with overgrazing the allegorical example as the tragedy of the commons[3]. We propose the term dis-closure.

To disclose means: “The action of making new or secret information known”, according to the Oxford English dictionary[4]. But besides the colloquial meaning it has in English, this disclosure has to be broadened by the Dutch meaning of “ontsluiting” (i.e. “unlocking”), often used for monuments. Dis-closing a monument means to protect, maintain and open a monument to visitors in a sustainable way. To emphasize this shift, I propose to use a hyphen: against the enclosures of the commons, the dis-closures of the commons. Dis-closing the commons then is not only the revelation or sharing of something that was secret or privatized, but also the protection and caring for a common. In any case we should keep the clarity of the concept of enclosure of the commons, which is their demise and destruction as commons. In fact, the enclosures of the commons and the nationalisations of common land (which in Belgium for instance happened as late as the first half of the 19th century), led to the forgetting and erasure of the very concept of commons from our collective memory.

Dis-closure of commons can take on very different shapes. We will have a look at some of them to give our proposed term some substance. We start with world heritage. Some heritage can only be preserved and protected by complete closure. An allegorical example of a common good of mankind is the cave of Lascaux, with it magnificent cave paintings, that has been closed off for the public after it became apparent that more visitors would eventually destroy this heritage. So it was closed and a replica was made: Lascaux II. To cater for the mass of tourists that makes a pilgrimage to this site, subsequently also Lascaux III and IV were made. This shows we can both keep the treasure and visit it. When the cave paintings were discovered at the Grotte Chauvet in the early nineties of the last century, the first decision was to close it to the public and immediately start to make a replica or simulacrum for visiting. This radical closure gives an idea of what dis-closure can mean for the debate on the commons and their protection. So this radical closure covers very well what David Harvey has in mind when he gives the example of the protection of the Amazonian. As for Van Eycks world famous ‘Lam Gods’ in the Sint Bavo’s in Ghent, a different solution was found: the original painting from 1432 remained in the same church, well protected behind thick glass and since 11 July 1986 also located in a different part of the church, i.e. the Villakapel. At the original location, in the Vijdkapel, tourists can look at a colour copy of the 15th-century polyptych. This enables showing both the interior as well as the back panels of the altarpiece, without refusing visitors to equally get a glance at the original. Whilst it is presented as a measure of precaution and protection of this world heritage as a sort of global cultural commons, is has also enabled to have even more (paying) visitors passing. It’s perhaps useful to remind that also in the case of Lascaux and Chauvet, I do not take into consideration the touristic exploitation. I just take them as pure examples of closure as protection.

An almost opposite example is hacking. In the tradition of hacking, the colloquial meaning of disclosure as revealing a secret and the meaning of the creation and protection and caring for the commons by sharing almost coincide. Hacking is a practice that reveals, gives back to the public information or tools that are withheld from it. That constitutes the beauty of activist hacking. The many leaks of late are good examples: Wikileaks, the Panama Papers, Luxleaks, etc. All of these have contributed to stir debate in society on profiteering and dark political and military schemes, like the invasion of Iraq and the subsequent torture practices at Abu Graib, for instance.

But hacking does not always have to be spectacular… I give the example of our book Heterotopia and the City[5]. For this book, I collaborated with my friend and colleague Michiel Dehaene, collecting the texts of a colloquium on the theme. All authors were paid by their institutions as participating in colloquia is what academics do, so they were more or less all paid by the taxpayer. We cleared the rights for the illustrations in the book and even designed the cover. So it was a free book so to speak. Then Routledge published it and sold it for €120 a copy. Of course, most of the copies were bought by university libraries, so this Routledge book was a second time subsided by the tax payer, for most university libraries are paid by public money. A good example of the so-called market logic in academia: enclosure of public funds. Socialisation of costs, privatisation of gains, the golden formula of capitalism. That business plan is of course repeated book after book (I just contributed to a new book on heterotopia and it will also cost €120).

By this business plan Routledge made the book almost inaccessible for the common reader/buyer (and even for the editors – ten copies at half the prize is still €600, quite an investment to hand out the book to friends and colleagues). Until an anonymous instance just hacked it and made if available for free, so now anybody, including myself and my students, can use our book for free. (Just type ‘heterotopia and the city’ in your search engine and it is all yours). That for me is a fine and fitting example of hacking as dis-closure. Re-appropriation of what was enclosed for private gain. The battle for open source knowledge sharing in academia is an epic in itself. The slow science movement has criticised this privatisation of knowledge, as knowledge should be a commons[6].

A different example of dis-closing also in the sense of opening up, revealing is Trage Wegen (slow paths), a Belgian organization that works on networks of ancient neighbourhood paths in the countryside to roam over. Trage Wegen is working on a network of these roaming paths, and it is literally opening up privatized small paths harking back to right to cross, habitual law, etc. So this sort of opening up, is certainly a good example of a dis-closure of a common[7]. A different example of dis-closure of landed commons is the co-housing or common living. Particularly the Community Land Trust or CLT is a true landed commons: the ground is property of the trust (or the government) and the apartments are property of an intensely coached group, and the trust also involves the neighbourhood, which is represented in the board. It has several aims: to go against gentrification, as the ground remains fixed, due to the split between ground and building parts, the apartments are cheaper and therefore accessible for lower incomes, and in the process a sort of community is formed that makes sure the larger neighbourhood is involved[8].

A wilder form of appropriation for dwelling is of course squatting. Squatting is, like hacking, a radical form of commoning: a re-appropriation of private property, a re-use of empty houses or buildings. Unfortunately, in recent times in most countries, also in Belgium, squatting has been criminalized, even if the needs for housing have considerably risen, not only in terms of number but also, and even more so, in terms of money, as the rents and real estate prices have risen to dangerous levels in almost all major cities. This combination of enclosure and subsequent criminalization of those who infringe upon the enclosure is somehow comparable to More’s example: first the commoners were bereft of their common lands and therefore source of subsistence, and subsequently heavily punished. Vagabondage was severely repressed and the punishment for theft was hanging. This double crime Thomas More witnessed, was according to me the true point of ignition of his book Utopia[9].

A popular form of dis-closure since the sixties, but with a significant rise recently, is temporary use. You could call is squatting with permission. The idea is that all sorts of socio-cultural organisations are given the time and space to experiment and offer all sorts of events and services to the neighbourhood during this temporary use. Toestand and even more so La Communa in Brussels are good examples: they fill empty buildings with intense social activities of local groups and curate all sorts of events. Dis-closure here means testing out possibilities, preparing the neighbourhood for transformations, trying to give the youth of the neighbourhood a place to do graffiti, skating, organizing concerts, film screenings, debates, etc. “NEST” in Ghent was another example, Time Lab made a sort of self-organising work and event space in the empty old public library for a year. It was a great success.

All these urban commons try to be open or half open, for closure is almost inscribed in the traditional commons, in the conception and case of Elinor Ostrom commons are for a particularly community, like irrigations systems, alp meadows, or fishing grounds. Free access and Free use would deplete the Common Resource Pool, as she called it[10].

Closure is indeed, beside scale, the Achilles heel of the commons, for you do not want gated communities to count as commons, or even worse: commons starting to resemble the logic of gated communities. This is not an abstract problem, as we have seen in the CLT’s, the community land trusts, where the ground itself remains the property of the cooperative trust, they try to involve the wider neighbourhood by have a third of the board consisting of people from the neighbourhood, exactly to avoid that this form of co-housing becomes a sort of gated condominium.

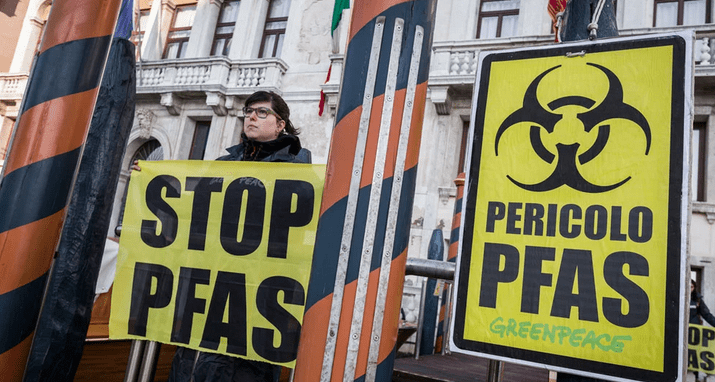

Beside all the local commons and the different forms of dis-closure people use to at the same time open up and preserve a commons, it is of course imperative to protect the global commons. Dis-closure as protection by an international legal order under the sign of the common good will be of utmost importance in this era called the Anthropocene, the era in which humankind is not only the predominant species, even in geological terms, but is also in the process of destroying the ecosystem. Particularly at the largest scale, dis-closure should be high on the agenda: the dis-closure of the biosphere. It is this sort of gigantic protection that Harvey was thinking of when giving the example of the Amazonian in his quote. Dis-closing the Amazonian would mean closing down the massive mechanisms of deforestation and protecting both the biodiversity and the livelihood of the local population and native tribes.

The legal commons (as divergent from the cooperative commons) that were founded in the ‘Charter of the Forest’, the appendix rediscovered by Peter Linebaugh to the founding text of anglosaxon law, the Magna Carta[11], can give an idea of the grander dis-closure we will need to protect and give access to the universal commons of the ecosystem in the Anthropocene (the age in which humankind has become a geological force), what has been called climate justice. The Charter of the Forest gave all commoners access to loose wood and fruits of the royal forests, the right to have a pig grazing, etc., but it was forbidden to hunt. This sort of right of access for subsistence and protection will be crucial to avoid the worst of overuse and depletion, resulting in the intrusion of Gaia as ticklish assemblage (to refer to Stengers and Latour[12]). We have to break away from ‘extractivism’[13] and ‘agrilogistics’[14]. The climate summits with the Paris agreements as faint hope are an attempt to make such a international protection of the biosphere, but it is all too little too late.

To conclude, I hope that the term dis-closure can help to avoid confusion in the debate on the struggle against the enclosures of the commons. In the Anthropocene that is now turning into a constellation of ecological disasters like climate change and loss of biodiversity, protecting the global commons, the biosphere will be of utmost, vital importance. Closure of the Amazonian, as Harvey suggests, is the scale of dis-closure we will need.

(with thanks to Annette Kuhk for her critical feedback and additions.)

[1] David Harvey, Rebel Cities. From the Right to the City to the urban Revolution. London – New York: Verso, 2012.

[2] Lieven De Cauter, ‘Utopia Rediscovered: A Redefinition of Utopianism in the Light of the Enclosures of the Commons.’ In: Achten, V., Bouckaert, G. & Schokkaert, E. (eds), ‘A Truly Golden Handbook’. The Scholarly Quest for Utopia. Leuven University Press, Leuven, 2016.

[3] I of course refer to the classic tale by Garret Hardin on depletion of a ungoverned open land by overgrazing and free riding: Hardin, G (1968). “The Tragedy of the Commons” in: Science. 162 (3859), pp. 1243–1248.

[4] https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/disclosure. Accessed February 2019.

[5] Dehaene, M. & De Cauter, L. (eds), Heterotopia and the City. On Public Space in a Postcivil Society. Oxford – New York: Routledge, 2008.

[6] Slow Science Manifesto : https://slowscience.be/the-slow-science-manifesto-2/

[7] Saavedra Bruno, Sofia, M., Parra C., Moulaert, Frank en Van den Broeck, Pieter. ‘Reclaiming space, creating a landed commons. Negotiating access through the Hoofse Hoek’. In: Van den Broeck, P., Leubolt B., Kuhk A., Moulaert F., Parra, C., Delladetsimas, P., Hubeau, B. (eds), Governing shared land use rights : conceptualising the Landed commons. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar publishing, 2019.

[8] For more on CLT”s see: https://cltb.be/fr/ accessed February 2019

[9] Lieven De Cauter, ‘Utopia Rediscovered: A Redefinition of Utopianism in the Light of the Enclosures of the Commons.’ O.c

[10] Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons, Cambridge: Cambridge university Press, 2015.

[11] Peter Linebaugh, The Magna Carta Manifesto. Liberties and commons for all, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2008.

[12] Isabelle Stengers, Au temps de catastrophes. Résister à la barbarie qui vient, Paris : La Découverte, 2013.

Bruno Latour, Face à Gaia, huit conférences sur le nouveau régime climatique, Paris : La Découverte, 2015.

[13] Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything, Capitalism vs the Climate, London/New York: Allen Lane (Pinguin Books), 2014.

[14] Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology, Columbia University Press, New York, 2016.